Exterior insulation and finish systems (EIFS) are proprietary wall cladding assemblies that combine rigid insulation board with a water-resistant exterior coating. Popular chiefly for their low cost and high thermal insulation performance, they are used across a range of construction types, from hotels to offices to homes.

Unlike traditional stucco, which is composed of inorganic cement-bonded sand and water, EIFS employs organic polymeric finishes reinforced with glass mesh. As an energy-efficient, cost-effective wall covering, EIFS is effective for both new construction and recladding applications. However, the successful use of EIFS depends heavily on proper design and sound construction practices. Without proper design and detailing, EIFS wall systems are prone to failure.

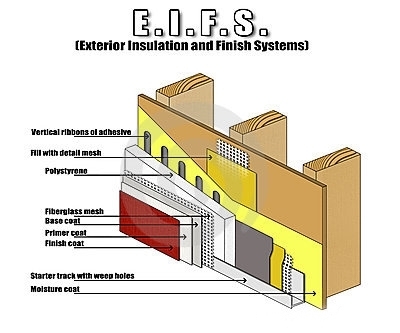

Elements of an EIFS wall assembly

EIFS are multi-layer systems that typically consist of six basic components:

- substrate—usually exterior gypsum board, oriented strandboard (OSB), or plywood;

- membrane or rainscreen (some systems);

- exterior insulation (adhesively or mechanically fastened);

- base coat—consisting of proprietary acrylic copolymer dispersions and powder additives;

- reinforcing glass fiber mesh; and

- finish coat, or ‘lamina,’—comprising copolymer dispersions, colorants, and stabilizers.

There are two major types of EIFS. The first, Class PB, represents the majority of EIFS used in North America.

Class PB (polymer-based)

Known as ‘soft-coat’ EIFS, Class PB systems use adhesively fastened expanded polystyrene (EPS) insulation with glass-fiber reinforcing mesh embedded in a nominal 1.5-3 mm (1⁄16-1⁄8 in.) base coat.

Class PM (polymer-modified)

‘Hard-coat’ EIFS were developed for improved impact resistance. Reinforcing mesh is mechanically attached to extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation, over which a thick, cementitious base coat of 6 to 9.5 mm (1⁄4 to 3⁄8 in.) is applied.

Direct-applied exterior finish system (DEFS)

DEFS is the exterior finish component of EIFS, excluding the insulation. Base and finish coats are applied directly to the substrate. Mainly used for soffits, stairwells, and high-impact-prone areas that do not require insulation, DEFS may be applied to cement board, concrete masonry units (CMUs), exterior-grade plywood, polyisocyanurate (polyiso) board, or other proprietary products.

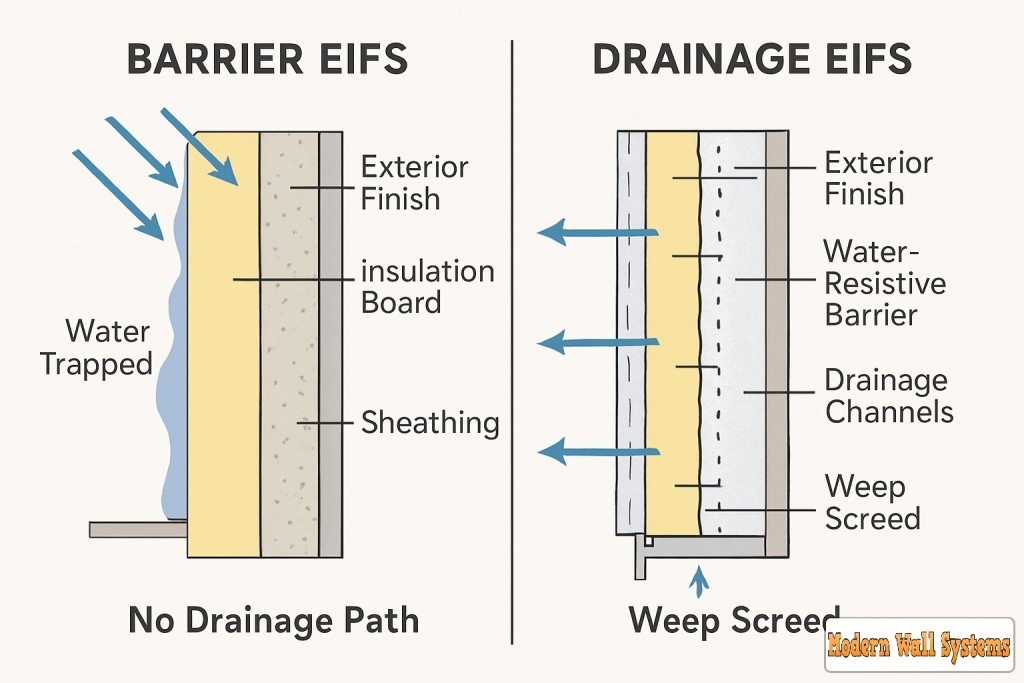

EIFS with drainage

Also known as ‘rainscreen EIFS,’ drainage-enabled EIFS is installed over a waterproofing barrier with drainage channels to remove incidental moisture behind the insulation board. Often, these channels are formed by applying adhesive in longitudinal strips or by using an insulation board with vertical grooves. The effect is similar to that of a cavity wall, where the space behind the exterior-facing drains or dries any moisture that penetrates the cladding. EIFS with drainage were introduced in 1996, following a 1995 class-action lawsuit involving widespread failure of traditional barrier EIFS.

Although EIFS with drainage addresses the water-intrusion problems of face-sealed EIFS, it is not a foolproof solution. Should the vapor barrier or moisture retarder fail, water can still enter the assembly. Therefore, air and water barriers must be designed to last the system’s service life.

Components of an exterior insulation and finish systems (EIFS) include:

(1) finish

(2) reinforcing mesh

(3) rigid foam

(4) adhesive

(5) substrate

(6) steel or wood stud

EIFS Failures and Fixes

Originally, EIFS were designed as a ‘perfect barrier’ system—one which provides waterproofing protection at the exterior face of the cladding. The idea behind barrier cladding assemblies is to create a face-sealed façade that repels moisture, keeping the building dry.

Unfortunately, barrier systems are rarely perfect. All it takes to compromise watertightness is a small breach in the exterior finish, such as cracks from expansion, sealant failure at joints, or impact damage. Once water enters a barrier system, it usually cannot exit. Water trapped in the wall can cause leaks, wet substrate, mold growth, deterioration of building components, and, eventually, the collapse of the weakened cladding.

Any number of deficiencies can lead to EIFS failure. The major culprits are poor workmanship, damp climate, impact damage, building movement, and incompatible or unsound substrate.

Poor workmanship

Sealant joints are a major source of problems with EIFS cladding. Incorrect selection or application of sealant (or sealants missing altogether), provides an easy path for water entry and premature deterioration. Inappropriate sealant may even lead to cohesive failure of the EIFS finish coat. Sealant applied to the finish coat instead of the mesh-reinforced base coat is a common source of problems.

Missing or improperly installed flashings create pathways for water infiltration. Door and window openings should incorporate flashings to direct water away from headers and sills. At roof/wall intersections, drip-edge flashings should be installed to channel rain away from the wall face.

Base coat thicknesses that do not meet the manufacturer’s guidelines are another typical source of trouble for EIFS façades. A base coat that is too thin provides insufficient waterproofing protection, whereas a base coat that is too thick may lead to cracking.

Reinforcing mesh that reads through at joint edges or terminations can indicate inadequate coating thickness. Alternatively, the mesh may have been insufficiently embedded in the base coat. Continuing the mesh-reinforced base coat around to the back of the insulation board, known as ‘backwrapping,’ is critical to providing continuous waterproofing protection at edges, penetrations, and terminations. Factory-formed track may be used at foundation terminations instead of backwrapping, when appropriate.

Aesthetic joints (V-grooves) aligning with insulation board joints can lead to cracks as the building moves. Mesh-reinforced base coat should be continuous at recessed features.

Window and door corners, like aesthetic joints, should not align with insulation board joints. ‘Butterfly’ reinforcement, whereby rectangular pieces of reinforcing mesh are laid diagonally at the corners of windows, doorways, and other openings, is important to prevent cracking.

Expansion joints are too often neglected in EIFS construction, but they are no less critical than in other cladding systems. Expansion joints should be used:

- at changes in building height;

- at areas of anticipated movement;

- at floor lines (particularly for wood-frame construction);

- where the substrate changes;

- where prefabricated panels abut one another;

- at intersections with dissimilar materials; and

- where expansion joints exist in the substrate or supporting construction.

Insulation board should not bridge expansion joints in masonry or concrete substrates. Instead, an expansion joint should be created in the EIFS insulation over the underlying joint.

Climate factors

A humid climate with limited drying potential can degrade some EIFS assemblies, particularly when the rate of wetting exceeds the rate of drying. Poor design and installation exacerbate this problem by allowing water to penetrate the cladding, while humidity prevents the walls from drying out.

The amount of rain deposited on a wall depends not only on climate but also on the structure’s architecture and siting. Building height, overhangs, exposure, and façade details all affect the path of rainfall, channeling more or less moisture toward the cladding.

Cold climates may also lead to premature system failure, particularly when EIFS coatings are applied at temperatures below the manufacturer’s design range.

Impact damage

EIFS consists of a thin, brittle coating over a soft substrate and is easily damaged by impact. Holes, dents, or scrapes can cause water infiltration, so it is prudent to provide additional reinforcement at susceptible locations.

Areas requiring impact protection should use heavy-duty mesh, typically 340 to 566 g (12 to 20 oz), rather than standard 127 g (4.5 oz) mesh. For outside corners, the design professional may specify a heavier corner mesh to prevent excessive wear and damage. Intricate decorative elements require a lightweight, flexible detail mesh, which conforms to fine contours and ornamental details while still providing some measure of impact protection.

Impact damage to EIFS caused by woodpecker activity and other physical impacts, resulting in compromised finish and potential moisture intrusion.

Design considerations

The performance and longevity of any cladding assembly depend on proper system design and installation, and EIFS is no exception. Sequential coordination of work is one way to avoid defects, particularly at intersections and terminations. The general contractor, framers, window installers, sealant contractor, EIFS installer, and other trades should be organized such that the work of one does not adversely impact the work of another. For large areas, a sufficient workforce should be on site to permit application without cold joints or staging lines. Whenever possible, EIFS application should proceed on the shaded side of the building.

Sealant joint and flashing design

The design professional is responsible for determining the appropriate joint size and location and specifying a compatible sealant. In general, low-modulus sealants that retain their properties under ultraviolet (UV) radiation are recommended for EIFS. Sealant selection should consider anticipated joint movement, substrate material, cyclical movement, and exposure to temperature extremes. To prevent premature degradation at the bond line, closed-cell backer rod should be used instead of open-cell backer rod, which tends to retain moisture.

At points where water can enter the wall (e.g., roof/wall intersections, window and door openings, and through-wall penetrations), it should be directed to the exterior with appropriate flashing. Flashing should be integrated with air seals, sealants, rough opening protection, and other waterproofing materials.

Surface texture anomalies

The phenomenon of ‘critical light’ occurs when natural or artificial light strikes a wall surface at an acute angle, less than 15 degrees, such that tiny surface irregularities cast a shadow. To minimize the negative aesthetic impact of critical light, the EIFS installer should remove planar irregularities, high spots, and shallow areas with a high-quality rasp (file with projecting teeth). Mesh overlaps should be feathered to minimize read-through, and a skim of base coat may be applied to blend laps. To correct critical light defects in existing EIFS, the design professional may specify reskimming the original finish coat with an appropriate base coat, followed by application of a new finish coat after the base coat has dried.

Cool weather application

Damage to EIFS components from low-temperature application may be undetectable in the short term, but tends to emerge later as coatings crack, flake, soften, and delaminate. For most acrylic and cementitious coatings, application is restricted to temperatures of 4°C (40°F) and above. Below the design minimum, these coatings will not develop proper physical and chemical strength, and they may not coalesce correctly to form a film.

When scheduling EIFS installation, one should avoid periods of the year when thermal cycling is highest, such as autumn, when temperatures are warm during the day and cold at night. Materials with controlled set times will cure more slowly in cold conditions—the project schedule will need to allow additional time for curing between coats. The ambient temperature and the surface temperature of the substrate—

which may be significantly lower—should be considered. It is advisable to warm certain substrates before application.

Patches and repairs to existing EIFS are particularly susceptible to cold-weather cracking because seasoned material is combined with new material that has not yet reached full strength. After the initial set, patch areas should be kept warm to promote curing and reduce thermal stress.

Key Precautions for Cold Weather EIFS

- Temperature Control: Maintain ambient and substrate temperatures above 40°F (4.4°C) for at least 24-48 hours after application for each component.

- Temporary Enclosures: Use tarps or enclosures to create a protected work zone that shields against wind and cold.

- Vented Heating: Use vented, fuel-fired heaters (like propane) to provide heat and prevent moisture buildup, ensuring fresh air intake and exhaust of water vapor.

- Material Protection: Store EIFS materials indoors and bring them into the heated enclosure before use to acclimate them.

- Ventilation is Key: Avoid kerosene heaters due to soot contamination; ensure proper ventilation to remove water vapor from the combustion process.

- Patience with Drying: Cold slows evaporation; allow for extra drying time between coats.

- Substrate Prep: Ensure the substrate is dry and warm before application.

Risks of Improper Cold-Weather Installation

- Improper Curing: Water-based components won’t cure properly.

- Delamination/Flaking: Poor bonding leads to system failure.

- Efflorescence: Salts can migrate to the surface.

- Freeze-Thaw Damage: Trapped moisture can freeze, damaging sheathing and coatings.

Quality control

Quality control in EIFS (Exterior Insulation and Finish Systems) is critical to the long-term performance, durability, and moisture resistance of the building envelope. Proper quality control ensures that materials are installed in accordance with manufacturer requirements, project specifications, and industry standards, reducing the risk of water intrusion, cracking, delamination, and premature failure.

Because EIFS relies on multiple integrated components—substrate preparation, weather-resistive barriers, flashings, sealants, insulation, and finish coats—small installation errors can lead to significant and costly issues. Consistent inspections, trained installers, and documented quality checks help protect warranties, minimize callbacks, safeguard the owner’s investment, and improve overall building performance.

Maintenance and repair

To keep EIFS looking and performing their best, building owners should implement inspection and maintenance practices to address incipient problems promptly.

Cleaning

EIFS finishes, and sealants should be inspected for damage or wear at least twice a year. EIFS should be cleaned thoroughly every five years—locations prone to algae and fungal growth may require more frequent cleaning. Options for EIFS cleaning include commercial detergent, pressure washing, or a trisodium phosphate (TSP) solution. Washing in cold water is recommended, as hot water can soften acrylic finishes. Difficult stains—such as those from wood, tar, asphalt, efflorescence, graffiti, or rust—may require sealing and re-coating.

Coating

Elastomeric coatings can provide a fresh appearance and added waterproofing protection for worn EIFS surfaces. However, such coatings may alter the texture, sheen, and vapor permeability of the original cladding. Existing sand finish with a small aggregate size may lose its texture after recoating. One should avoid dark-colored coatings, which absorb heat and tend to crack. To verify compatibility of an elastomeric coating with the existing EIFS finish coat, most manufacturers recommend testing as per ASTM D3359, Standard Test Methods for Measuring Adhesion by Tape Test. Typically, EIFS manufacturers produce their own elastomeric coatings, which are designed to be compatible with their cladding systems.

Refinishing

To address EIFS damage or persistent stains, resurfacing may be necessary. First, the installer should clean and dry the area, then trowel a skim base coat to fill voids in the surface. Once the base coat is dry, apply a new finish coat per the manufacturer’s instructions. When color-matching a new finish to an old one, a physical sample should be used, as age and exposure may have altered the original color. Differing application techniques may prevent refinished areas from blending completely with the existing finish, so resurfacing an entire panel to a termination usually produces better results than a smaller patch.

Flashing and sealant repair

Common points of water entry, including window and door perimeters, expansion joints, intersections with dissimilar materials and roofs, penetrations, and terminations should be periodically checked. Removing worn sealant may damage the existing EIFS, which must then be repaired and allowed to dry before new sealant may be installed. The design professional should confirm the new sealant is compatible with the surface of application.

EIFS damage repair

Depending on the depth and severity of EIFS damage, repair may entail removal and replacement of finish, base coat, reinforcing mesh, and even insulation board. Prolonged and pervasive water infiltration may also require replacement of substrate materials and possibly of the entire wall, including structural support members. For puncture or impact damage, such as dents or holes, the manufacturer should be consulted for instructions, particularly if the system is still under warranty. Shopping plazas, for instance, are vulnerable to damage from store signs that have been removed without repairing fastener holes. One should check with the manufacturer to determine whether such punctures void the warranty.

EIFS performance

If correctly designed, installed, and maintained, EIFS provide durable envelope protection. The oldest systems in the United States were installed in the late 1960s, and some are still in service. For those concerned about the long-term viability of EIFS in light of the series of cladding failures in the 1990s, a 2006 study from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) should put many of those apprehensions to rest.

Over a 15-month period, ORNL tested a number of cladding types, including brick, stucco, concrete masonary unit (CMU), cementitious fiber board, and EIFS, in the challenging mixed-coastal climate of Charleston, South Carolina. Of those wall systems tested, the best-performing was an EIFS assembly including a liquid-applied water-resistive barrier coating and 100 mm (4 in.) of EPS insulation board. The study validated vertical ribbons of adhesive provided an effective means of drainage within an EIFS wall assembly.

The ORNL study demonstrates that the new generation of EIFS successfully rectifies problems inherent to earlier systems. When designed with attention to moisture management, modern EIFS can be a reliable, cost-effective option for an energy-efficient building envelope.